Looking at the human digestive tract, the direction from the mouth to the anus is taken as caudal.

- Betaserc® (Betaserc® )

- pharmacokinetics.

- Guideline

- Applications in human anatomy

- indication of directions

- limbs

- vertical plane

- Deepen your knowledge

- Concentration on the preparation

- 1. lateral and medial.

- 2. distal and proximal

- Lung wings and segments

- right lung

- upper lobe

- upper lobe

- lower lobe

- What does a CT scan of the lungs show?

- Structure of the bite

- Viola's international bifacial chart

- Characteristic injury of the lower jaw

- Causes of Metatarsophalangeal Fold Syndrome

- Symptoms of Metatarsophalangeal Fold Syndrome

- The levels of the human body. types of movement.

- The basic action of the limb joints in yoga:

- Equipment for lateral canthomy

- Step-by-step description of the technique

Betaserc® (Betaserc® )

Round, biconvex, white or colorless tablets with bevelled edges, an opening on one side and engraved '289' on both sides of the opening.

The mechanism of action of betahistine is only partially known. There are several possible hypotheses supported by preclinical and clinical data:

1. Effects on the histaminergic system

Partial H1-histamine and antagonist of H3-Histamine in the vestibular nuclei of the CNS, has negligible activity against H2-receptors. Betahistine increases histamine metabolism and release by blocking presynaptic H receptors3receptors and reduces the number of H3-receptors.

2. Increased blood flow to the cochlea area as well as the entire brain

According to preclinical studies, betahistine improves blood flow in the vessels of the inner ear by relaxing the precapillary sphincters of the inner ear vessels. Betahistine has also been shown to increase cerebral blood flow in humans.

3. facilitating central vestibular compensation

Betahistine accelerates the return of vestibular function in animals after unilateral vestibular neurectomy by accelerating and facilitating central vestibular compensation through antagonism with H3-Histamine receptors. Recovery time after vestibular neurectomy in humans is also shortened by treatment with betahistine.

4 Stimulation of neurons in the vestibular nuclei

Betahistine dose-dependently reduces the generation of action potentials in the lateral and medial neurons of the vestibular nuclei. The pharmacodynamic properties observed in animals support a beneficial therapeutic effect of betahistine on the vestibular system. The effectiveness of betahistine has been demonstrated in patients with vestibular vertigo and Meniere's syndrome, achieving a reduction in the severity and frequency of vertigo.

pharmacokinetics.

Absorption. After oral administration, betahistine is rapidly and almost completely absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract. After absorption, the drug is rapidly and almost completely metabolized to the metabolite 2-pyridylacetic acid. The plasma concentration of betahistine is very low. Therefore, pharmacokinetic analyzes are based on measuring the concentration of the metabolite 2-pyridylacetic acid in plasma and urine.

When the drug is taken with food, the maximum concentration ( CMax ) drug in the blood lower than in the fasted state. However, the total absorption of betahistine is similar in both cases, suggesting that food intake only slows the absorption of betahistine.

Distribution. Binding of betahistine to plasma proteins is less than 5%.

biotransformation. After absorption, betahistine is rapidly and almost completely metabolised to the metabolite 2-pyridylacetic acid (which has no pharmacological activity). CMax of 2-pyridylacetic acid in plasma (or urine) is reached one hour after administration. The half-life of the elimination phase (T1/2 ) is about 3.5 hours.

Excretion. 2-pyridylacetic acid is rapidly excreted in the urine. After administration of a dose of 8-48 mg, approximately 85 % of the initial dose are recovered in the urine. Renal or intestinal excretion of betahistine is low.

linearity. The rate of elimination remains constant after an oral dose of 8-48 mg, suggesting that the pharmacokinetics of betahistine are linear and that the metabolic pathway involved remains unsaturated.

Guideline

In animals, the head is usually at one end of the body and the tail is at the other end. The end of the head is called in anatomy skull, cranialis (Cranium - skull) referred to, the caudal end is called caudal, caudal (cauda – tail). The head itself is aligned with the animal's nose, and the direction towards its tip is called rostral, rostralis (rostrum – beak, nose).

The upward facing side of the animal's body, opposite to gravity, is called the dorsal, dorsal (dorsum, back), and the opposite side of the body closest to the ground when the animal is in its natural position, i.e. when running, flying or swimming ventrally, ventricular (stomach – abdomen). For example, the dorsal fin of a dolphin is located dorsaland the cow's udder is on the ventral Page.

The same terms apply to the limbs: proximal, proximalfor a point less far from the hull, and distal, distalisfor a more distant point. The same designations for internal organs refer to the distance from the origin of the organ (eg: 'distal part of the jejunum').

Law, dexter, i Left, sinisterPages are labeled as they would appear from the point of view of the animal being examined. The term homolateral, less often ipsilateral refers to a spot on the same page while contralateral – is on the opposite side. Bilateral – designates a place on both sides.

Applications in human anatomy

All descriptions in human anatomy are based on the assumption that the body is in an anatomical posture, that is, the person is standing upright, shoulders down, palms facing forward.

The areas closest to the head are called upper…and further … lower .. upper , superiorcorresponds to the concept of skulland inferior lower, corresponds to the notion of caudal. anterior, anterior, i posterior, posteriorcorrespond to the terms ventrally i dorsal. In addition, the terms anterior i rear is incorrect for four-footed animals, the term should be used for ventrally i dorsal.

indication of directions

Formations closer to the medial plane are medial, medialisand those farther away are lateral, lateralis. The formations lying in the medial plane are called medial, median nerve. The cheek, for example, is located lateral to of the nostril, and the tip of the nose is median Structure. When an organ lies between two adjacent structures, it is called a intermediary, intermediate.

The units closer to the hull are proximal in relation to those more distant, more distant. These concepts also apply to the description of organs. For example, distal end of the ureter into the urinary bladder.

Central – located in the center of the body or an anatomical area;

peripheral – outside, away from the center.

When describing the location of organs located at different depths, terms are used: deep, profound, i superficial, superficialis ..

terms external, external, i internal, internalused to describe the location of structures in relation to various body cavities.

The term visceral, visceralis (viscerus) means belonging to an organ and its immediate vicinity. A parietal, parietal (paries – wall), denotes belonging to the wall. For example, visceral . The pleura covers the lungs during the parietal Pleura covers the inside of the chest wall.

limbs

The surface of the upper limbs in relation to the palmaris is denoted by the term palmaris, palmaris, the surface of the lower limbs in relation to the soleus by plantaris, plantaris.

The edge of the forearm on the side of the spoke is called radial, radialisand on the ulnar side ulnar, ulnar. On the shin, the edge on which the shin rests is called shin, tibialisand the opposite edge, on which the fibula lies, is called peroneus, fibular.

vertical plane

Please remember that there is no level in anatomy with that name!

To avoid confusion, when listing the planes in anatomy, you should never start with the horizontal plane. It may happen that you automatically say the word 'vertical' and your conversation partner/teacher will then think that you have skipped anatomy.

It's best to talk about the horizontal plane at the very end, after the sagittal and frontal planes.

Deepen your knowledge

Let's use another illustration of the great Da Vinci. Try to determine in which plane we are looking at the skull and in which plane it is sawn. You can find the answer among the vocabulary in this article.

Concentration on the preparation

1. lateral and medial.

Lateral = far from the conditional center of the body. Medial means close to the middle of the body. That's very easy to remember - there's a well-known English word 'middle' that means 'middle'. So remember that anything closer to the center of the body, i.e. in the middle, is medial. Anything that is lateral and farther from the center of the body is lateral.

Let's look at an example. The collarbone (clavicle) has an acromial end (etremitas acromialis), which we locate in the drawing and mark in blue. Next we locate the sternum and mark its cervical notch (incisura jagularis) in red. We will compare the acromial end of the collarbone and the cervical notch of the breastbone (incisura jagularis) based on their position:

The cervical notch occupies a distinctly medial position since it is very close to the center of the body. The acromial end of the clavicle is to the side of the cervical notch because it is farther from the center of the body than that notch.

2. distal and proximal

In the explanations of anatomists or surgeons, one often hears expressions such as 'distal phalanx fracture', 'proximal ileal canal', 'move the skin proximally'. What do you mean with that?

'Distal' means 'far from the origin, from the upper part, from the body'. Proximal' means 'close to the origin, from above, from the body'. Put simply: proximal = near, distal = far.

Keep this in mind in a very simple way. The word 'distal' has the same root as the word 'distance'. 'Far away' means 'far away'. Accordingly, 'proximal' means 'near'.

The simplest example is that the nail is on the distal phalanx of the finger. I marked the distal phalanx in red and the proximal phalanx in blue. Elemental, isn't it?

Lung wings and segments

right lung

upper lobe

Upper segment, S1 -. Located behind the second rib of the rib cage. Lung segment 1 has airways with a total length of about 2 cm. This segment is connected to S2 by an airway.

The posterior segment, S2-. relative to the apical segment, segment 2 is located dorsally (downward) at the level of the 2nd to 4th ribs. This segment is respiratoryly connected to S1, via the vascular branch to S3, and to the pulmonary artery.

The anterior segment, S3-. lies anterior between the 2nd and 4th ribs. Segment 3 of the lung includes the superior branch of the pulmonary artery.

Most infectious and inflammatory lung diseases, such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, and granulomatosis, originate from lesions in the upper lungs. Since the adjacent sections of the lungs – artery and bronchus – are connected, it is important to identify the type of infectious agent and start treatment in time to prevent further spread of the disease.

In emphysema, this is also where the alveoli (airways) are located.

upper lobe

Lateral segment, S4 -.Located in the front part of the armpit between the 4th and 6th ribs.

The medial segment, S5Located in the front part of the chest at the level of the 4th and 6th ribs.

So, segments 4 and 5 of the lungs are located at the same level in the medial-anterior part and are crossed by tubular bronchial branches and vessels. Tumors and metastases are more common at this level than in the upper lungs.

lower lobe

Upper segment, S6 -.Projections on the lower half of the scapula: from the middle to the horn, at the level of ribs 3-7. The blood supply in segment 6 of the right lung is via the artery – an extension of the lower pulmonary artery.

The medial basal segment, S7 -.also known as the 'cardiac' segment because it is closer to the diaphragm on the inside and closer to the right atrium. A branch of the vena cava is located near it. A high-resolution CT scan is the only scan that provides a good view of lung segment 7.

What does a CT scan of the lungs show?

Studies show that lung lobes, such as B. segments, are not reliably detected on X-ray images, even if they are performed on a digital scanner with additional contrast enhancement.

Computed tomography of the lung makes it possible to examine the organ 'from the inside', so to speak, by sequentially scanning each lobe (increments of up to 1 mm) with high resolution. In this way, the radiologist can determine the boundaries of the lobes and formulate a correct conclusion for the treating physician - pulmonologist, internist or otolaryngologist - who has the final say in making the diagnosis and prescribing the therapy.

Computed tomography (CT, MSCT) of the lungs shows:

- Segmental structure of the respiratory organ and the smallest pathological changes;

- airway integrity and patency;

- condition of the cardiac septum, inflammatory processes;

- circulatory disorders, thrombosis, vasoconstriction (CT with contrast medium);

- lymph node enlargement;

- Local inflammatory processes;

- tumors;

- metastases;

- Mechanical anomalies.

As part of the CT examination algorithm, the radiologist assesses the anatomical elements of the lungs:

- soft tissues;

- bone tissue;

- diaphragm and sinuses;

- lung roots;

- bronchial tree;

- mediastinal organs;

- Interstitium and architecture of the pulmonary matrix.

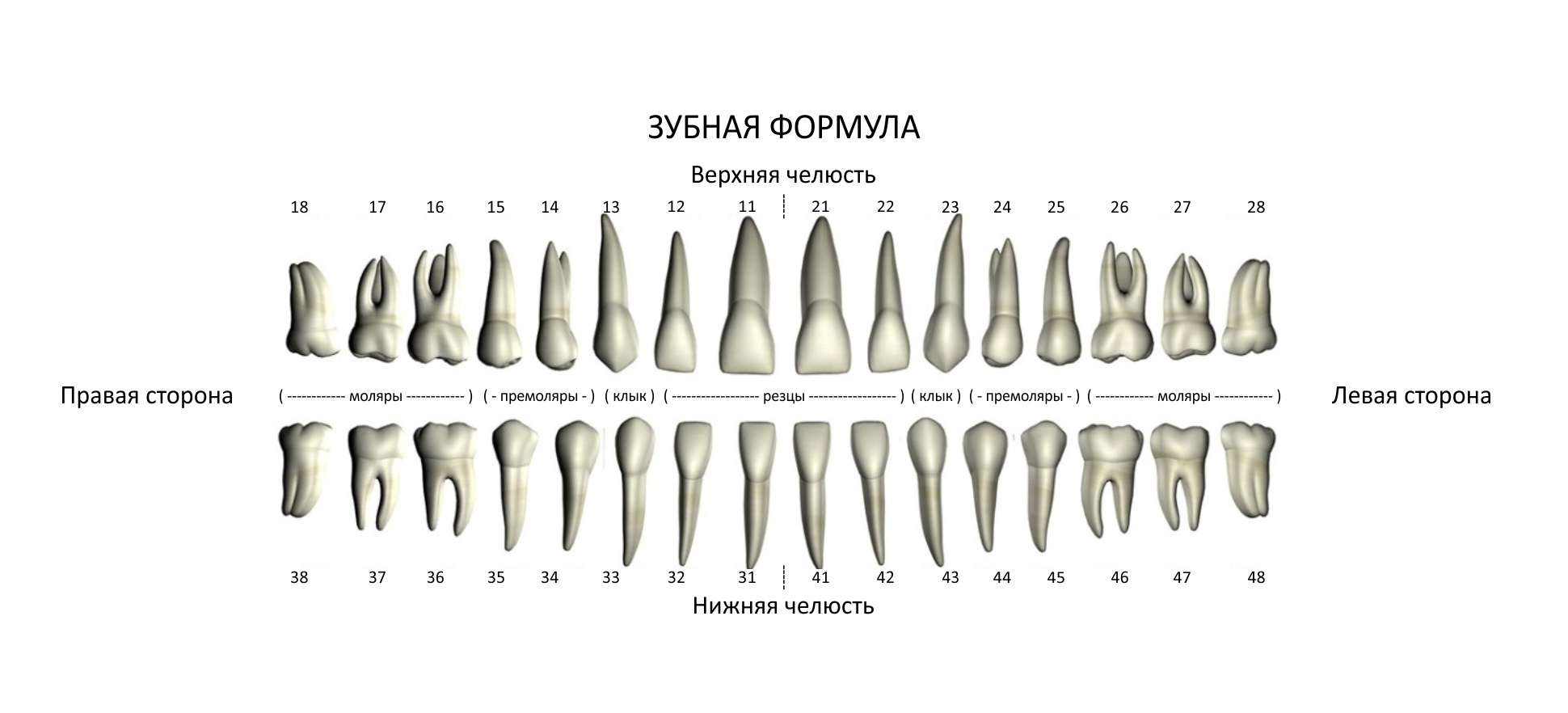

Structure of the bite

The teeth in the jaw are arranged in such a way that the crowns of the teeth form rows of teeth (arches) – above and below. The jaw line functions as a whole and is a dynamic system that changes with age. The adult dentition consists of 16 teeth. The arrangement of the teeth is usually recorded in the form of a dental chart in which individual teeth or groups of teeth are usually identified by numbers.

Viola's international bifacial chart

All teeth are divided into 4 sectors (counterclockwise when viewed from the inside):

- Maxillary teeth on the right side (central incisor 11, second incisor 12, canine 13, first premolar 14, second premolar 15, first molar 16, second molar 17, third molar or wisdom tooth 18).

- Maxillary teeth on the left side (21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 as on the right side).

- Mandibular teeth on the left (31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38).

- Mandibular teeth on the right side (41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48).

A similar numbering from 51 to 85 is used for children's teeth or they are denoted by Roman numerals.

In the center of the dentition are the incisors and canines that bite, and on the sides are the premolars and molars that grind and grind food. The incisors and canines are single-toothed and single-rooted teeth. The premolars and molars are multi-rooted teeth with multiple roots.

The height of the crowns decreases from the incisors towards the posterior teeth, especially in the mandibular dentition. In the upper jaw, the buccal cusps of the molars are higher than the palatal cusps. The stability of the dentition depends on the position of the teeth and the direction of their crowns and roots.

The interdental contact zones are near the incisal edge of the anterior teeth and near the occlusal surface of the posterior teeth. Below the approximal surfaces is a triangular space filled with gingival papillae (interdental papillae).

During chewing, the teeth have the character of a uniform arrangement. The pressure exerted on a tooth is not only transmitted to the alveolar area via its roots, but also via the interdental contacts to the neighboring teeth.

With age, the contact points of the teeth wear out, but the continuity of the dental arch is not affected, although the teeth can be shortened by up to 1 cm. The unity of the dentition is also ensured by the periodontium and the alveolar ridge. The communication between the individual teeth is served by the marginal interdental ligament, which, as a strong bundle of connective tissue fibers, connects the cementum of one tooth with the cementum of the other above the apex of the interdental septum. This bundle facilitates mesial or distal movement of a tooth, resulting in movement of the adjacent teeth.

Characteristic injury of the lower jaw

The lower jaw is not monolithic. The presence of canals and areas of different bone density leads to typical traumatic injuries.

The following areas are most commonly fractured:

1. the neck of the posterior (articular) dental process.

2. the fossa of the canines or premolars (small molars). 3.

3. the angle of the lower jaw.

Sudden sideways movement (eg, from a punch), opening your mouth excessively, or trying to bite something hard can result in another type of injury: temporomandibular dislocation. The joint surfaces shift and prevent normal movement of the joint.

The jaw needs to be repaired by a specialized trauma surgeon to prevent overstretching of the surrounding ligaments. The danger of this injury is that the dislocation can periodically reoccur during sudden movements.

The temporomandibular joint is exposed to constant stress throughout life. It is used when eating and speaking and is important for facial expressions. Lifestyle, diet, and systemic musculoskeletal disorders can affect the condition.

Causes of Metatarsophalangeal Fold Syndrome

- swelling

- Pleural tissue hypertrophy (thickening)

- decreased elasticity

- fibrous changes

- secondary synovitis

- chondromalacia

- Overuse of the knee joint - cycling, jumping

- traumatization

- surgical intervention

- chronic inflammation (synovitis)

Rarer causes are rheumatoid arthritis, bleeding into the joint associated with hemophilia, volumetric changes in the knee

Symptoms of Metatarsophalangeal Fold Syndrome

Clinical signs of the syndrome include:

- Pain in the front of the knee that worsens when getting up from a seated position

- a cracking sound when bending

- audible phenomena such as snapping, crunching, popping, etc.

- discomfort when pressed

- Swelling, edema and swelling in the knee joint

- Painful squatting, climbing stairs, jumping after standing for a long time

- Restriction of joint mobility

The levels of the human body. types of movement.

- • flexion and extension(flexion-extension). This is a movement in the sagittal Level. – abduction reduction(Abduction-Adduction). This is a movement in the front Level. – outward rotation i inside(lateral and medial rotation). This movement in horizontal Level.

Flexion (inclination, rounding) -. A movement in the sagittal plane in which the front surfaces of the upper and lower body approach each other.

Extension (flexion) -. Movement in the sagittal plane in which the front surfaces of the upper and lower body move away from each other.

Lateral flexion (side bending, side tilt) -. Movement in the frontal plane associated with a lateral tilt of the spine.

Rotation (rotation, twist, turn) -. Movement in the horizontal plane that causes rotation of the spine.

Also: axial extension (axial traction) -. A movement directed along the vertical axis that lengthens the spine by straightening all the bends simultaneously.

The basic action of the limb joints in yoga:

Dorsiflexion -. A movement that decreases the angle between the back of the hand and the forearm (often referred to as wrist extension).

palm flexion -. A movement that decreases the angle between the hand and forearm (also often referred to as wrist flexion).

Rotation. The movement in which the spoke and ulna cross is called pronationThe movement in which the bones of the elbow and ulna cross each other is called supination.

diffraction Forward movement of the arm in the sagittal plane.

stretch The backward movement of the arm in the sagittal plane.

abduction Movement of the arm away from the body.

abduction Movement of the arm towards the body.

outward rotation. An outward movement of the arm so that the arm rotates outward.

inward rotation The movement of the arm in which it rotates inward.

Elevation - (English). The upward movement of the scapula in the frontal plane.

lowering The downward movement of the scapula in the frontal plane.

stretch Movement in the horizontal plane that moves the scapula away from the spine.

convergence Movement in the horizontal plane with the shoulder blade close to the spine.

plantar flexion is. A movement that decreases the angle between the sole of the foot and the back of the shin (sometime called foot flexion).

Dorsiflexion (dorsiflexion) is. A movement that decreases the angle between the posterior surface of the foot and the forefoot (sometimes referred to as foot extension).

inflection A movement that decreases the angle between the lower leg and thigh.

Stretch A movement that increases the angle between the lower leg and thigh.

diffraction Forward movement of the leg in the sagittal plane.

stretch Movement of the leg backwards in the sagittal plane.

Equipment for lateral canthomy

Local anesthetic (such as 1%ige or 2%ige lidocaine solution with adrenaline), small hypodermic needles, and a small (about 3 mL) syringe

Timely detection of orbital compression syndrome is important to minimize the duration of retinal ischemia and to perform canthomy or cantholysis. An ophthalmologist should be consulted, but this should not delay the operation. Also, since the diagnosis of orbital compression syndrome is purely clinical, surgery should not be postponed until imaging studies have been performed.

The surgery is painful. A patient who is conscious, disoriented, or lacking in contact may need regional nerve blocks, sedation, or mechanical immobilization to prevent movements that could damage the eyeball during the procedure. Children may need general anesthesia during the procedure.

Step-by-step description of the technique

All preliminary steps should be performed as soon as possible, including a gross assessment of visual acuity, an examination of the eyeball, and sometimes a simple procedure and flushing of the side lid area.

Place all instruments on a tray near the head of the bed so everything is within reach and you don't have to call for help.

Prep the skin with an antiseptic such as povidone, iodine, or chlorhexidine; do not let the antiseptic get into the eye; Cover the surgical field with sterile towels (sheets).

Inject 1 ml or 2 ml of adrenaline-containing local anesthetic into the area of the lateral canthomy.

Using a needle or hemostat, disrupt the tissue from the lateral angle of the orbit to the orbital rim, at intervals of 20 seconds to 2 minutes. Destruction of this tissue helps reduce bleeding and facilitates inspection of the incision site in the event of extensive post-traumatic swelling.

Use iridectomy scissors to make a 1-2 cm incision from the lateral corner of the eye to the edge of the orbit (canthotomy).

The inferior and sometimes both branches of the lateral canthal ligament (cantholysis) should be severed. Most experts recommend starting with the inferior ligament. Lift the lower part of the lateral edge of the eyelid. Using scissors pointing away from the eyeball, locate and remove the affected root. The division of the inferior ligament supports the movement of the scissors. If the tendon is still intact, you will feel a tremor, like pulling an Achilles tendon.

As a next step, some experts recommend routine superior ligament dissection. Others recommend re-evaluation to mitigate the effects of orbital compression syndrome (eg, by measuring intraocular pressure); superior ligament dissection is recommended if effects persist.

Read more:- The lateral side is.

- The so-called lateral foot bone.

- What is distal?.

- The medial surface of the tibia.

- Personalized media inserts.

- Bump on the side of the child's foot.

- side of the foot.

- The intercondylar syndesmosis is the.